- Value of Champions League media rights rises in US and France, holds steady in UK

- Strong start to cycle belies pessimism about soft market but tough tests lie ahead

- Mediapro complaint in France puts spotlight on sales methodology

There are two truisms in the sale of sports media rights which at first glance appear difficult to reconcile. One is that every market has a unique set of characteristics and the value earned is contingent upon those characteristics at the moment the rights are sold. The other is that the early deals in a market-by-market sales cycle create a psychological benchmark which affects how sales in the following markets play out.

The more sophisticated rights sellers do their homework on every market where they pitch their tent. But they still put great faith in benchmarks. And perhaps none more so than Team Marketing, the sales agency for the commercial rights to Uefa’s club competitions.

The order in which global markets are approached for the sale of the media rights to the Champions League, Europa League and, as of this cycle, the Europa Conference League is determined with scientific rigour, with those markets likely to deliver the best results coming first.

Team’s decision to launch early in the US for the 2021-22 to 2023-24 cycle did not come as a big surprise. Soccer in the US is still in a growth phase and will remain so until the North American-hosted 2026 Fifa World Cup and a cycle or two beyond. But going early in the UK and France raised eyebrows. Each, for its own reasons, looked like a potential banana skin.

The deals done last month in the US and France look like a strong vindication of Team’s choices, with the caveat that the process in France has become mired in controversy. The deal in the UK invites further scrutiny.

In the US, Uefa secured a 67-per-cent increase in the value of its English-language rights and 43 per cent for its Spanish-language rights. CBS acquired the English-language rights for about $100m (€90m) per season and Univision the Spanish-language rights for a fee thought to be close to $50m per season. Long-form agreements are still being finalised for both.

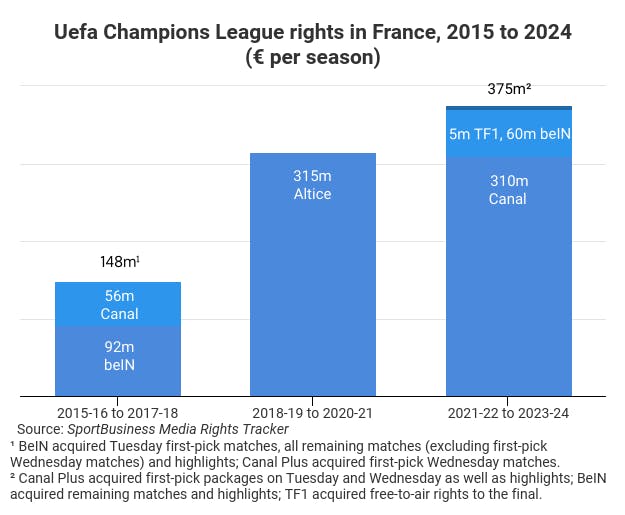

In France, the rights were won by pay-television operators beIN Media Group and Canal Plus, with commercial broadcaster TF1 picking up the rights to the final. The total fee of €375m per season is almost 20 per cent more than telco Altice pays for the Champions League in the current three-year cycle.

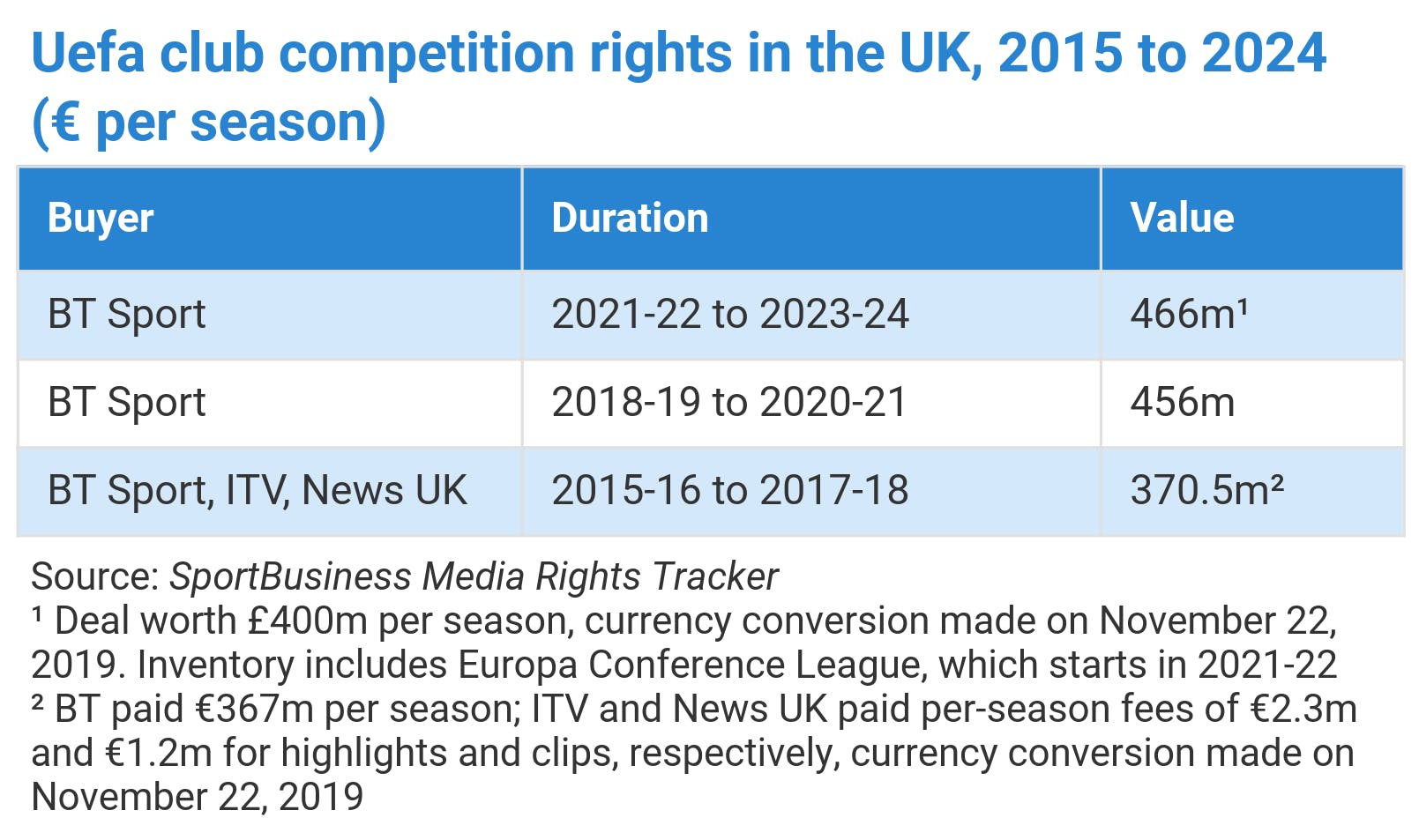

The UK delivered another massive deal, albeit it with a modest 1.5-per-cent bump. Telco BT renewed for a further three years, paying €466m per season.

In football parlance, Uefa is three up after 15 minutes. And reports of the death of the sports-rights market appear to have been greatly exaggerated.

But European football’s governing body knows the remaining 75 minutes could still see an heroic comeback by that amalgam of giant-killers: piracy, cord-cutting, mature pay-television markets, collusion and the changing consumption habits of younger fans. The champagne will stay on ice in Uefa’s Nyon headquarters and Team’s Lucerne offices until the final whistle blows.

And many experts see this early sequence of deals not as a repudiation of the market’s Cassandra figures but as confirmation of a trend that has been under way for years: the polarisation of value between a small number of must-have properties and everything else.

Consultant Pierre Maes, who was responsible for buying sports rights for pay-television group Canal Plus in the Benelux countries, the Nordics and Poland from 1996 to 2002, argues the results to date are not surprising.

He tells SportBusiness: “In every single European country you get two strong properties. The strongest is the local league, usually football. Then it’s the Uefa Champions League. And the gap between these two and the rest is getting bigger and bigger.”

Maes, author of the 2019 book Le Business des Droits TV du Foot, which examines what he calls the “explosive bubble” around football rights, adds: “You can’t extrapolate a general rule for football rights from three very different markets, but Uefa and Team will be happy with the numbers so far. They’ve done a fantastic job, particularly in France.”

Flat is the new up

Going early in the UK is perhaps the most intriguing choice Team made for this cycle. The market fundamentals are strong but there has been little competitive dynamism since rival pay-television platforms Sky and BT opted for collaboration over confrontation. It was always likely to be the biggest single deal, as it is in the current cycle, but did not look like a market that would deliver a large percentage increase. And it is percentage increases, rather than absolute value, that sellers look to as benchmarks.

One executive with long experience of selling rights into the UK provides the following reading: “Launching now meant two things. They knew they weren’t going to get a bloody nose and they felt that if they waited, market conditions were more likely to get worse than better.”

Team would have known exactly what it was doing, he argues, from its pre-sale talks – sometimes referred to as “warming up” the market.

“The product has been performing well and Team knows exactly what numbers BT has been doing. Team has sophisticated calculations about how BT can capitalise on the rights, directly and indirectly. On the basis of their models, they know BT’s business case. In talks with BT they would have got a sense of whether that was realistic as an expectation this time. So, they would have put the choice to BT: we can launch now, you can secure the rights through to 2024 and don’t have to think about it – but you have to do the right thing. Or we can wait, which means insecurity.”

While flat looks curious as a marker for the rest of the industry, it makes sense in the UK, the expert believes. “The percentage increase in the first two markets has always been crucial to Team in terms of the following markets. But the fear of doing worse in a year’s time was strong. The competitive dynamics are not good and are slowing down. The UK is a big worry market for Uefa. To do badly in the UK is the worst possible signal. Securing a very important deal – and that sheer amount of revenue – was an imperative for Uefa, even if it was a minimal increase percentage-wise.”

Playing safe in France?

Mediapro’s threat to take legal action against Uefa for the way in which the rights auction was handled – claiming it was the legitimate winner – has taken some of the sheen off Team’s success in France. It is unusual for a losing bidder to go public with such threats but not unprecedented in France. When Altice picked up the rights last time, beIN and Canal Plus complained to Uefa that they should have won.

There are two implications contained in Mediapro’s complaint that will make uncomfortable reading in Nyon. The first is that there was some form of impropriety, and Uefa prides itself on its transparency. The second is that by not prolonging the process to allow Mediapro back in for a further bid, Uefa has left money on the table. Those clubs who believe they could do a better job than Uefa of running an elite European club competition will have made a quiet note.

As Maes points out: “The real question in all these deals is whether the clubs are happy. The pressure of the clubs on Uefa between now and 2024 will be huge. One thing is certain: if tomorrow there was a European Super League it would not suffer any market correction because it would be the absolute number one property in the world.”

There are also those who ask whether Mediapro has scored an own goal. By claiming publicly that it outbid beIN and Canal Plus and still didn’t get the rights, the Spanish production house is inviting the market to ask why. Maes believes that many observers – rightly or wrongly – will draw the same conclusion: financial security.

For rights-holders, he says, security is not just about bank guarantees. “The guarantee from beIN and Canal Plus is their client base. They have millions of clients who are paying, today. Mediapro has nothing. It is the clients who are underwriting the deal. They are the best guarantee you can have. That number of clients gives a rights-holder both financial security and wide exposure.”

In June 2018, Mediapro acquired live rights to France’s top domestic league, Ligue 1, for €780m per season. The deal takes effect from the 2020-21 season, when Mediapro plans to launch subscription channels. Adding Champions League rights would have put the company in a very strong negotiating position with third-party carriers. For now, the company has no platform in France.

Maes suggests that Team has been “very clever” in using Mediapro’s aggressive arrival on the French market “to get a good price from the others” for the Champions League.

If Mediapro is right in its claim to have outbid beIN and Canal Plus in each of the two rounds of bidding, the eventual outcome arguably points to the degree of flexibility which Team and Uefa allow themselves in the auction process.

Unlike, say, the Premier League, Team and Uefa have never had a fixed threshold – a percentage difference between the two highest bids – for choosing a winner. Broadcasters have asked for this over the years and Uefa and Team have discussed it many times but always concluded that it should be left to Team’s discretion.

An executive who has been involved in several Champions League auctions argues that there is too much discretion in the tender process and adds that “allegations of phone calls after the deadline are a bad look” for Uefa.

Another rights expert counters that this kind of flexibility is necessary, especially in markets where there is collusion between bidders. “Having a target – say, a 10-per-cent difference – which generates an automatic winner is risky. You could have a market with three players, and they are all lowballing because they have spoken to each other. One might be offering a lot more than the others, but you still know they’re taking the piss, trying to engineer an outcome . You need flexibility to consider all options at that point, whether to go to a second and third round or abort the process completely.”

Team is currently considering its options in multiple other markets, including Germany, another litmus test territory. When Germany, Italy, Spain and the Middle East and North Africa are done, a clearer picture will start to emerge.

Uefa is used to cycle-on-cycle increases of over 30 per cent for its club competitions, but, according to one executive familiar with the sales process, would probably settle for 10 to 15 per cent this time. That total will become the most important benchmark of all – the one clubs will be guided by when shaping European club football from 2024 onward.